Will Billy Wagner Get a Final Year Bump in Hall of Fame Voting?

Wagner only needs a small bump in his vote share to win induction to Cooperstown. Fortunately for him, most final year candidates get such a bump.

On Monday, the Baseball Hall of Fame distributed ballots for this offseason’s Hall of Fame voting. And the big story for Astros fans is whether Billy Wagner get over the 75% threshold required for enshrinement. Last January, Wagner fell agonizingly close—only 5 votes short at 73.8%.

Voting for the Baseball Hall of Fame can be aggravating and bewildering in the best of times. I follow it closely and am well aware of its maddening inconsistencies, shifting standards and arbitrary decisions. As an example of this, see this skeet from my GoGoAstros podcast compatriot Andy Tomczeszyn.

In Hall of Fame voting, lots of things seem to matter, the electorate is small, the number of deserving candidates is often greater than the limit of 10 votes. As a result, it can be hard to identify voting patterns and predict results.

For example, let’s look at Wagner’s vote totals across the nine previous times he’s been on the ballot, which you can see in the Figure below. For his first three years on the ballot, he got very few votes—right around 11% each year. In 2019, he has a slight bump to 17%. And then, he suddenly starting accelerating in his vote share?

What happened? Apparently he became a better pitcher between 2019 and 2020 despite the fact that he had now thrown a big league pitch after retiring after the 2011 season. Which seems, as mentioned, maddening and arbitrary.

But if you follow these vote counts over the year, this pattern is pretty common. Players tend to rise up in their vote share over time, especially players whose Hall of Fame case is not open and shut.

For example, in Wagner’s first year on the ballot, he finished 5 votes ahead of Gary Sheffield. Sheffield rose up to 64% of the vote last year. Heck, in 2017, Wagner finished 4 votes ahead of Scott Rolen, who rose up to get the 75% of the vote he needed for enshrinement in 2023.

What explains these rises in vote share? Primarily, it comes from sets of voters who limit themselves to a handful of votes each year regardless of the merits of the candidates. Apparently, they think that if a whole bunch of people get inducted each year, it would reduce the value of the honor of induction. But if you spread it out over years, that’s better…for reasons.

So Wagner’s rise looks like Rolen’s, which looks a lot like Larry Walker’s rise, which looks a lot like Edgar Martinez’s rise, which looks a lot like Tim Raines’s rise. You can see the similarity in the chart below, which shows the vote total for each of those players across their years on the ballot. There are different individual vote patterns, but collectively, each starts out very low and rises to above 75%, with Wagner close to it.

You’ll notice something about the vote totals for Walker, Martinez, and Raines. Each reached the 75% threshold in their 10th year on the ballot. This is notable for two reasons. Wagner is going to be on the ballot for the 10th time this offseason. And the 10th year is the final year on which a player is eligible on the regular Hall of Fame ballot.

In short, this is Wagner’s final chance to get to win induction through this manner. It’s his last chance.1 But that it is his 10th and final year is likely a boon for Wagner.

Despite the inconsistencies of Hall of Fame voting, there is another established pattern. Candidates in their 10th year tend to get a final year bump. Hall of Fame voters may be inconsistent, but they are collectively a bunch of softies. Their hard calculations tend to give way to sentiment in a player’s last go round.

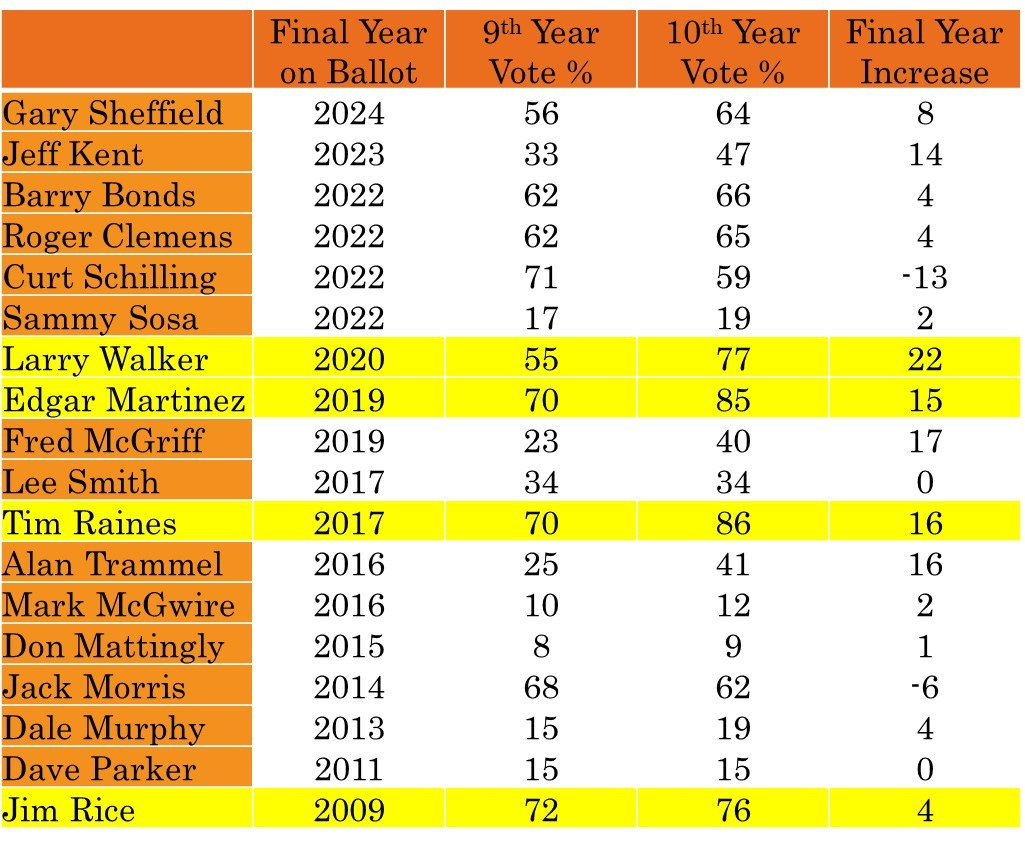

That table below shows the evidence for the final year bump. It shows the vote share received by players in their 9th and 10th years on the ballot, and the increase in the final year in the right hand column.2 I included all players in their final year going back to 2009. I also highlighted in yellow the four players who made it in during their final year on the ballot—Walker, Martinez, Raines, and Jim Rice.

The pattern is not always positive. Curt Schilling lost votes due to what can euphemistically be called antagonizing voters by being a jackass. Jack Morris lost votes due to a crowded ballot. And Lee Smith and Dave Parker stayed the same. But the rest all got bumps.

How big? On average, these Hall of Fame candidates did 6.10 points better in their final year on the ballot. Take away Schilling—whose candidacy lagged for non-baseball reasons—and it goes up 7.2 percent.

Wagner just needs a bump of 1.2%. Some final year candidates got a large bump—in addition to several inductees, Alan Trammell and Jeff Kent got double digit bumps. Other bumps were more modest.

But Wagner just needs a modest bump to win induction this year. It won’t take much for him to get to Cooperstown. Just a few sentimental voters giving him extra consideration in his final year on the ballot.

It has happened for most candidates in the past. And if it does for Wagner, he’ll win induction.

This is not fully correct. Candidates who do not win election can later by chosen by special committees that evaluate candidates from particular eras of baseball history.

In 2014, the Hall of Fame shortened the time allowed on the ballot from 15 years to 10 years. For players voted on before that, the 9th year total is actually their 14th year total and the 10th year is the 15th.