Why is Jim Crane Going Along With This?

The Proposals and Tactics of MLB Seem to Benefit the Smallest Market Owners. What Do Other Owners Get Out of MLB's Hardball Tactics

Today, Commissioner Rob Manfred announced what we knew was coming for months. Despite their being four to go before the scheduled Opening Day, Manfred was canceling it, and the first week of play for the 2021 season. And today’s announcement (and the usual litany of false statements that litter a Manfred public statement) reminds us of what the owner’s negotiating position has been for months—they are ready, and possibly eager, to cancel games in April in an effort to achieve their goals in the strike.

As Andy McCullough wrote today in The Athletic:

The MLB-imposed deadline will make official what Manfred’s 30 bosses have telegraphed for the past three months: The owners don’t care if you want to watch a full season of baseball.

Or as Evan Drellich wrote in the same publication:

They could have postponed Opening Day a long time ago.

The tactics of the MLB’s owners have been clear for a long while now—delay and do the minimum necessary to clear the legal requirement that they “bargain in good faith.” The owners waited 43 days after the lockout they imposed to “jump start the negotiations,” have declared based components of the CBA (time to salary arbitration, time to free agency, and revenue sharing formulae) off-limits from negotiation.

Saturday provided the the clearest demonstration of how little the owners are trying to reach an agreement with the players right. After a new proposal from the players that offered major moves on issues such salary arbitration and competitive balance tax (CBT, the technical name for the luxury tax), the owners countered that afternoon by agreeing to increase the CBT threshold by $1 million…in just one year.

There was some movement by the owners on Monday and the agreed to extend their fake deadline by a day. But by Tuesday, when the owners moved not at all on key issues while making a “best and final offer,” it was clear this gambit was part of a ruse designed for the owners and their hired hands to score a PR victory and claim they made the last offer. Some bought it. Most journalists did not.

The tactics used by the owners have been intransigence, but to what ends. As noted, the owners have demanded no changes in time to arbitration or free agency. They have pushed for exceedingly small increased in a player’s minimum salary. But the real sticking point for the owners seems to be those CBT thresholds. They owners have proposed increasing the lowest threshold from the $210 in 2021 to $220 million in 2022. And then it will gradually go up to $230 million by the end of the proposed CBA. That’s less than a 2% increase per year…in a sport which is averaging a 10% growth in revenues this century.

And the focus on CBT helps to clarify what the owners’ true proposal is…that the amount of money they pay to the players stays constant, while all of the sports’ revenue gains in the near future increase the bottom line for the owners. In short, the owners are proposing that they get everything and the players get crumbs.

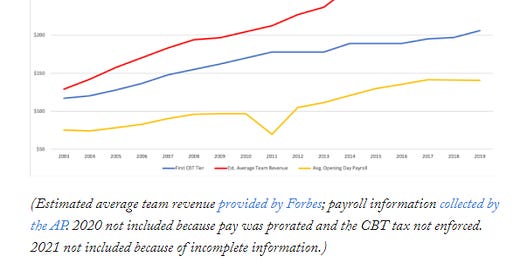

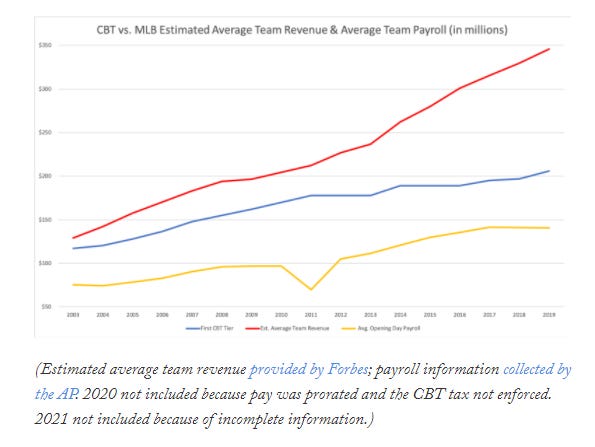

You can get a sense of how this has worked in recent years from this chart published in The Athletic earlier this year. In blue is the lowest CBT threshold, which is increasing only slightly in recent years. In yellow is the average payroll, which has actually started to go down in recent years.1 And is red is average team revenues (as estimated by Forbes). Unlike the other two lines, this one is increasing rapidly in recent years.

The owners have looked at these numbers and said “We’re making more money than we ever have before.” And then like Veruca Salt, they have decided they want the whole world

But there is a catch to this analysis and the way that I have written up the labor battle between owners and players—not all owners are the same, and not all players are the same. And different set of owners and players may prioritize different elements in this negotiation.

The players are a large group of just under 1,200 different individuals who come from different cultures and places on the globe and who are at different points in their career with different levels of future earning potential. As a result, we would expect that they have different perspectives on the lockout and different levels of willingness to go endure the loss of games (and revenues). At the moment, the players have maintained a united public front in support of their negotiators and their goals.

But so have the owners. Or, more precisely, we have heard no public statements from owners at all. None objecting to the extreme tactics of those negotiating on their behalf. If there is dissent, it is being expressed in private.

But is there dissent among the owners? There are good reasons to expect some set of owners to object to the strategies being employed on their behalf. In an excellent column posted on Saturday night, Ken Rosenthal asked

“Who is running this show anyway? The small- and mid-market clubs seemingly are dictating the league’s hard-line positions, particularly on the luxury-tax thresholds and penalties.

Who benefits if MLB creates a harder cap that falls behind increases in the cost-of living? The answer seems to be teams that run low payrolls such as the Pirates and the A’s. They, in the words of Jonathan Judge of Baseball Prospectus, “don’t want to spend more money but they also don’t want to be outspent.” One result of a low CBT threshold is that their higher revenue division competition like the Cubs and Angels will be compelled to trade high priced veterans to stay under the tax, or to pay money that gets distributed in revenue sharing money.

And who is hurt by the willingness of the small market owners to cancel games to keep payrolls capped for higher payroll team? Well, teams with higher payrolls that are butting up against the CBT. Teams like our Astros.

In 2021, the Astros ran a payroll of $208.8 million, according to Roster Resource. Look above and you’ll see that the luxury tax threshold was $210 million, and that is not a coincidence. The Astros front office clearly structured their payroll in 2021 to stay under the $210 million threshold (c.f. the incentive and bonus provisions of the Jake Odorizzi free agent contract, the Joe Smith for Rafael Montero portion of the Kendall Graveman for Abraham Toro deal, and adding Austin Pruitt to the Yimi Garcia deal).

Their payroll will likely decline in 2022, but they will again butt up against the threshold in 2023 and the near future as the salaries of young stars like Yordan Alvarez, Kyle Tucker, and Cristian Javier will increase as they enter the salary arbitration process. Unless of course, the threshold gets raised significantly.

The Astros are not alone in this situation. In 2021, the Phillies, Yankees, Angels, Red Sox, and Mets all had payrolls within $8 million of the de facto hard cap. Each of these teams would benefit from increasing the CBT threshold—the Mets because it would reduce their luxury tax bill in 2022, the Phillies and the Angels because they still have holes to fill on their 2022 roster, etc.

The owners of these teams—some large markets and some are decidedly upper-middle class (which is where I would put the Astros right now)—have competitive needs to increase their payroll. They also have economic needs to play baseball.

Teams make money when games are played, and lose money when they are not played. While we do not know the finances of most baseball teams, we do know the finances of the Atlanta Braves. The Braves are owned by Liberty Media, a publicly traded company, and they must release profit and loss statements to comply with federal securities law.

Liberty filed its most recent financial report and it showed the Braves made lots of money in 2021—taking in nearly $6 million per game played, and recording a profit of $104 million. In the 2nd fiscal quarter of 2021, the Braves took in $216 million in revenues and made a $54 million operating profit. In the second quarter of 2020, the Braves generated only $5 million in revenues. The difference—the Braves played no games in the 2020 2nd quarter due to the pandemic.

We do not know the Astros financials, but I would guess they are in a similar boat as the Braves. They have a good and popular team that will attract fans to the ballpark, driving revenues into Jim Crane’s wallet. Some of those revenues can be plowed back into the ballclub with little effect on the overall bottom line of Crane.

This leads to the question—why is Jim Crane going along with this? And another questions—why is Liberty Media going along with this? and the owners of the Yankees, Dodgers, Red Sox, and Phillies.

The strategy of the “owners” seems dictated by small market teams and their desire to avoid arms races for spending, and to create ways to increase their profits by reducing their biggest expense—player payroll. You can see why owners in small markets like Bob Nutting of the Pirates wants this system. And you can figure out why a team known for its front office incompetence like the Rockies would see themselves closer to the Pirates than the Astros or Braves. But Why do the teams in bigger markets and/or who have large payrolls right now because they employ good players?

One answer is money—billionaires like it and they did not get to be billionaires by spending a lot of money. The owners strategy seems risky because it has the potential for a high payoff—getting the union to cave and allow the owners to make off with a huge windfall.

But that calculation would seem to butt up against two realities. Teams will lose revenues on a daily bases because games are cancelled—and that revenue loss would fall most heavily on more competitive teams with large season ticket bases and fan bases clamoring to see games in April.

The second reality the owners’ calculation butts up against is that to get the union to cave, the union needs to crumble from within because it is riven by its own factions. But again, we have seen none of that from the players. A number showed up today to the MLBPA’s press conference to support their side. The social media response of players was again strong and supportive of the union, with no signs of dissent. And the MLB put out a statement this afternoon which said the lockout “is, in fact, the culmination of a decades-long attempt by the owners to break our Player fraternity.

The question for owners like Jim Crane is this—how much lost revenue should they take before they start urging Rob Manfred and the league’s negotiators to back off their extreme tactics and actually look to strike a deal. At what point with Crane, and Liberty Media, and the Steinbrenner Family, and John Henry of the Red Sox (and Liverpool FC) and the owners of teams like Giants, Cubs, White Sox, and Phillies start putting pressure on their colleagues to get a deal done?

So far, the answer is after games are already lost. Hopefully, the actual answer is soon, very soon.

The chart ends in 2019. Full data are not yet available for 2021 (though player payroll again went down). The authors excluded 2020 because it was 2020.