The Development of Young Players Is Essential for Front Offices, and The Cause of the Lockout

Teams Have Increased Playing Time for Players With Little Service Time, Increasing Profits for Owners and Tensions for the Players Association.

Last week, I wrote about how, after years of being on a similar track, the paths of the Astros and Cubs are have started to diverge. And I explained the reason for the divergence—the Astros have “developed a number of regulars [in recent seasons], including some of the roster’s biggest stars…The Cubs have developed few everyday players, and those that they have developed have tended to be pretty average.”

I included a section titled “Why Young Players Are So Valuable” which noted that “[t]he structure of baseball’s financial system makes is imperative that team’s develop young players” because that financial system allows teams to "pay players a fraction of their value.”

Players only receive fair market value for their services when they reach free agency, which does not happen after they accrue 6 years of service time. From their debut through year 3, 1teams can essentially play players a minimum salary. From years 4 through 6, the arbitration process increases a player’s salary, though never to the rates he will see as a free agent.

Baseball’s Financial System Incentives Using Young Players

I wrote last week’s article from the perspective of the front office. Teams benefit from developing young players because it is the highest value proposition. More production for less pay is a formula for profits in every industry, including baseball.

But if we examine this system from the player’s side, we see that the system rewards longevity but not productivity. Players are most valuable to management when they are paid the least.

And by examining baseball’s salary system in this way, one can see why the players and owners did not come to an agreement on a new Collective Bargaining Agreement by the December 1 deadline. Teams are incentivized to give plate appearances to players with less service time. In doing so, owners have hoovered up a larger and larger share of the funds in the game.

Salaries Have Plateaued Because Teams Are Using More Young Players

I’ll sketch out here in more detail how the salary system has pushed us to the current labor stoppage.

The first thing to note is that salaries are stagnating. The chart below tells the story in broad strokes. The average salary went up in major league baseball for years, until 2017, when it started stagnating.

An AP story from this April found that “The average major league salary dropped 4.8% to just under $4.17 million on Opening Day from the start of the previous full season in 2019. The average has fallen 6.4% since the start of the 2017 season, when it peaked at $4.45 million.”

What is the cause of the stagnation? One hypothesis is that revenues for the sport have also stagnated and salaries reflect that reality. People have been saying “Baseball is dying” for a century now; maybe they are finally right.

I am skeptical that this hypothesis is correct. We don’t know for certain that revenues and profits have stagnated. But in 2020, the Mets sold for $2.45 billion and the Kansas City Royals sold for $1 billion. So either the businessmen who bought these teams are terrible at their job, or they expect to make big profits from their investments.

Instead, it appears the stagnation in salaries for players has been the result of decisions by front offices to give more playing time to players with little service time.

At TheScore.com, Travis Sawchick ran the numbers and found that “the average service time of MLB players was 4.79 years in 2003 and fell to 3.71.

In particular, teams are relying more and more on players who haven’t even reached eligibility for arbitration. In a different article, Sawchick wrote that “that 63.2% of all players to step on the field in 2019 (the most recent year we have complete, full-season data from the MLBPA) had less than three years of service time.”

It is difficult for teams to reduce the playing time of star level players. They create value whether they are paid minimum salaries like Vladimir Guerrero or have signed huge free agent contracts like Bryce Harper. But it is much less difficult to reduce the playing time of average or below average players, of which there is a large supply.

Russell A. Carleton explain the logic in a recent article:

As the talent pool increases, there comes a point where there are more people who could do the job “well enough” than you have available slots. The chances that one of them who isn’t currently spoken for is a young player who would do roughly the same job for cheaper goes up. Why spend money on a 30-year-old fourth outfielder when there’s a 23-year-old who will do the same job for less?

The system allows them to pay an enforced minimum wage to a certain subset of players, and they’ve found a way to structure their rosters so that they can employ as many of them as possible.

Teams are relying more and more on players who cannot get fair market value for their contract. Those who reach free agency can still get paid the market rate for their services (c.f. the free agent frenzy in the month of November), but the average player feels the squeeze.

That AP article quoted above says that “[t]he median salary -- the point at which an equal number of players are above and below -- is $1.15 million, down 18% from $1.4 million two years ago and a drop of 30% from the $1.65 million record high at the start of 2015.”

These are the stakes of the lockout. The owners have tilted the status quo in their direction over the last several CBA negotiations. Thanks to the changes in the practice of front offices, the owners have been able to take a bigger share of the pie in baseball and the players are taking less.

Rob Manfred described the work stoppage as a “defensive lockout” and what the owners are defending is their money.

All of this analysis is important to the Players and their leaders. If they want to increase their share of the MLB’s revenues and direct more of it to players with less service time, they’ll need broad solidarity across their membership. And they’ll need to be more shrewd at the negotiating table than in recent CBA negotiations.

The union has often focused on free agency as their major focus in negotiations—getting free agency for the players is the major accomplishment of the Player Association in its history. But some analysts have recommended a different focus in this year’s negotiation.

Sawchik advocated for a significant increase in the minimum salary to benefit the majority of MLB players—those with less than 3 years of service time. “While owners can avoid participating in free agency and arbitration, they can't avoid paying minimum wages,” reasons Sawchik.

Marc Normandin posits that in a contest between “a shorter path to free agency and one to arbitration, but there is no contest” that the MLBPA should focus on arbitration. “More players would be impacted by the quicker route to arbitration, and it would do a better job of rebalancing the pay scale.”

Why Should Fans Care?

But these are priorities for negotiators for the players union. Why should worry about this as fans?

On option is not to care. We fans have little to no influence on how the money pie gets split up between the owners and the players. It’s perfectly fine just to want the lockout to end in time for Opening Day to be played as normal.

But I do care. As a ticket buyer, MLB.tv subscriber, TV viewer and dude who owns a lot of Astros shirts, I make a small contribution to MLB’s revenues. And I’ve always preferred that money go to the players—they are the ones who are providing me the entertainment I seek.

Or to put it another way, if the owners all went away tomorrow, the players would almost certainly be able to reconstitute themselves into a league and get the TV networks to agree to air their games. If all the players went away, we’d be back in Spring Training 1995. And no one wants that again—ever.

And that has been my position in baseball labor disputes for decades now. But I feel more strongly on the player side today due to the trend I identified here that a larger share of the revenue is going to the owners, and not to the players. The wrong dudes are getting the money and I’d rather it go back the other way.

We also should use the data I presented above about the preponderance of minimum salary players to understand the real context of the lockout. The players who have the most at stake are these minimum salary players, and the the frequent description of baseball labor disputes as a conflict between “millionaires versus billionaires” obscures more than it reveals. Some of the players are millionaires, but a majority are not.

And finally—and most relevantly to me as someone who writes about baseball—we should be aware of the implications of the language we use to discuss baseball. As I noted above, I wrote my article last week about how the Astros development of young players from the standpoint of the front office. James Click and the front office were succeeding at their job because they were able to develop players they did not have to pay at anything close to market rates. This is a common theme here at Orange Fire, because I tend to focus more on how to acquire players.

But the concern with this focus is that I adapt the perspective of the front office not just in player acquisition, but in focus on making profits for Jim Crane. Again, I’d rather the players get the money, rather than Jim Crane’s great-great grandchildren. And I need to make that clear to my readers. And I hope that others will do the same in their conversations, social media posts and texts about baseball.

Regardless of each of our personal attitudes about the lockout, the stakes are clear. The owners are taking a larger share of the revenue pie. They have done this in large part by employing more and more players at or near the minimum salary. The lockout is about whether than can keep doing so.

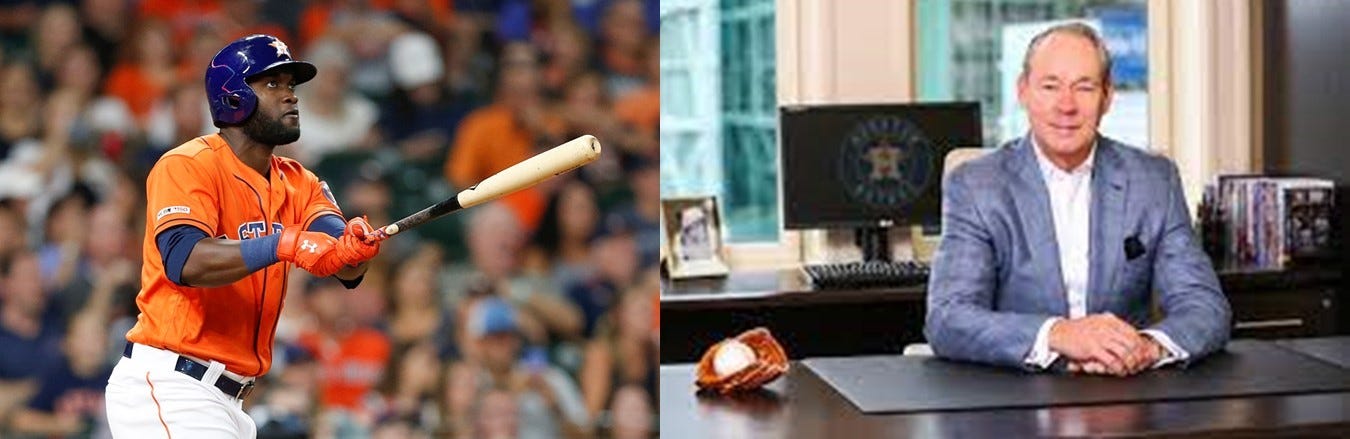

A share of second year players are eligible for arbitration under the “Super 2” provision of the CBA. Teams have learned to manipulate the service time of the top prospects so that the Super 2 group is usually made up of less expensive middle relievers and utility men. For example, the Astros kept Yordan Alvarez in AAA until June 9, 2019. And from a front office standpoint, this strategy worked. The Astros easily won the AL West in 2019 and Alvarez missed the Super 2 cutoff this year by 3 days.