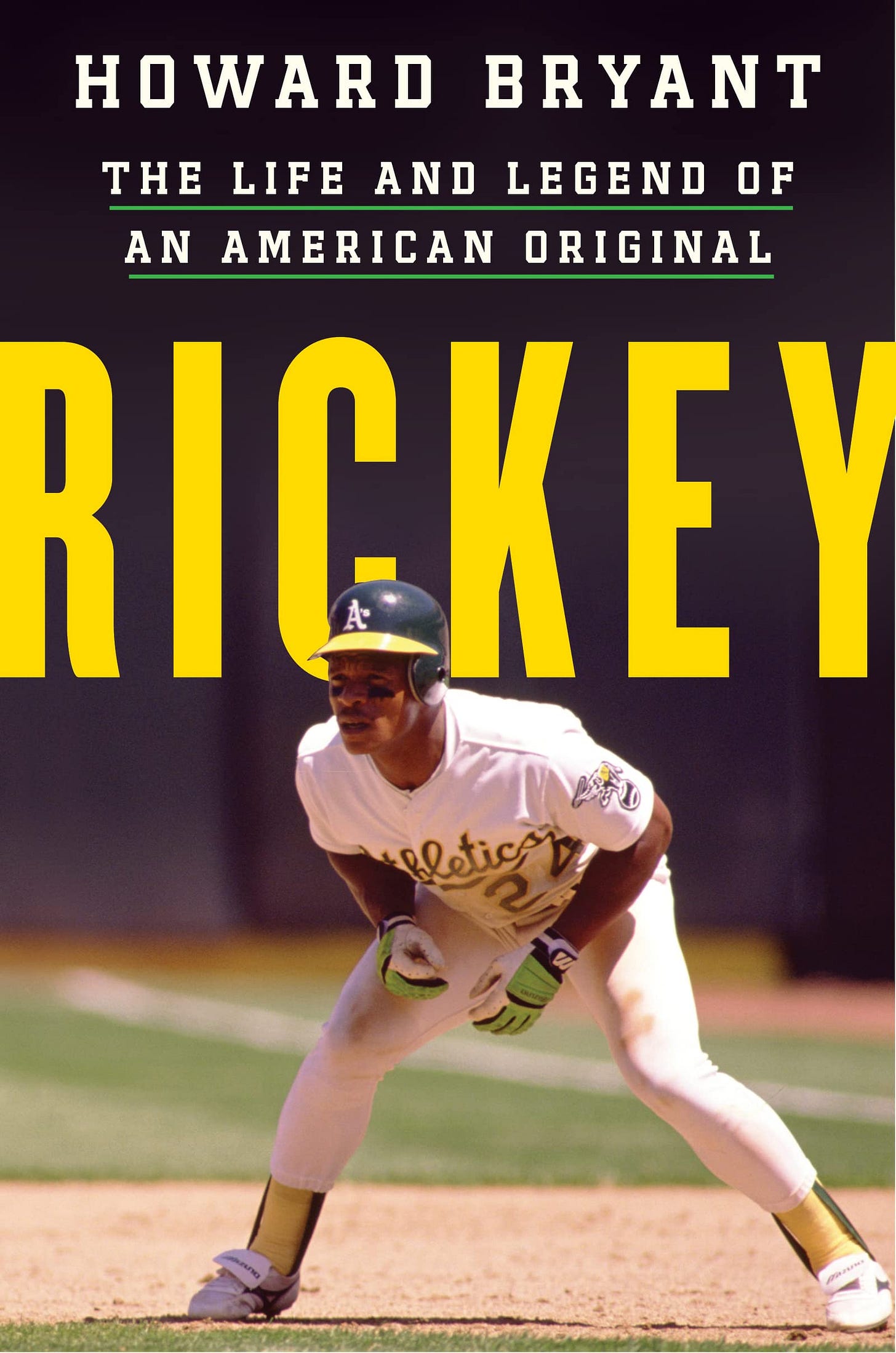

#RootRootRead. RICKEY: The Life and Legend of an American Original by Howard Bryant

How did Rickey Henderson go from egoist and clown to legend? A new biography shows that Henderson didn't change, but our understanding of how race works and how baseball is played and analyzed has.

When I was in high school, Rickey Henderson was most known for his ego. The epitome of this was on May 1, 1991, when Henderson broke Lou Brock’s record for most career stolen bases, and in the ceremony immediately after the record base theft, Henderson declared “Today, I am the greatest of all-time.” That night, Nolan Ryan threw his 7th career no-hitter and the joy that Henderson was taken down a peg was palpable.

When I was in my 20s, Rickey Henderson was most known as a clown. The epitome of this was the famous story that developed when a late career Henderson signed with Seattle. The story involves veteran first baseman John Olerud, who, due to having suffered a brain aneurysm in college, wore a batting helmet when he played in the field. Henderson, the story goes, went up to Olerud one day and said, “You know, we had a guy who wore a batting helmet on the field when I played in Toronto.” “I know, Rickey,” Olerud replied. “That was me.”

In my 40s, Henderson is a legend. The epitome of this is that the Oakland A’s have named the playing surface at the Coliseum Rickey Henderson Field. The logo below hangs on the outfield fence to mark the park, and to honor not only the greatest player to play for the A’s on that field, but also the local hero made good.

How did this transformation happen? How did Henderson go from egomaniac to clown to legend? This was the question I most wanted answered this summer as I read Rickey: The Life and Legend of an American Original, written by Howard Bryant. What accounts for this transformation in Henderson’s reputation?

I believe there are three sets of changes that help explain the transformation in perceptions of Henderson.

1. American society (read white American society) has transformed to have a more complete understanding of racism as a structural, as opposed to a legal, phenomenon.

2. Baseball is played differently today, as the flashy elements of “Rickey Style” that so irked the media and fellow players in the 80s and 90s have become a more commonplace element in a game that has embraced the style of its Latin and African-American stars.

3. The way the media thinks about baseball today is different than in the 80s. The analytic revolution has focused baseball analysis more on numbers and less on perceptions, to the benefit of players with great numbers and lousy media relations skills like Henderson.

I explore how each of these elements has changed the perception of Henderson over the decades. While Henderson, his style, and his playing record have not changed over time, how we understand ballplayers has. That we understand Henderson today as a legend and not an egotist or clown seems one clear benefit of these changes.

Race

Bryant roots Rickey in the story of the Great Migration, the massive movement of African-Americans out of the rural South and into the urban north and Pacific Coast in the middle of the Twentieth Century. Henderson’s family moved from Arkansas to Oakland in the early 1960s, at the end of long set of migration of African-American from the small towns of the southwestern parts of the Confederacy to work in the shipyards and railyards of Oakland. Oakland’s black community also provided a place for heightened athletic competition and achievement for the sons of these migrants, producing stars like Bill Russell, Frank Robinson, Joe Morgan, and, coming at the tail end of the migration, Henderson.1

The story of the Great Migration, its transformation of African-American culture from a rural to an urban one, its exposure of the structural nature of American racism, and its effect on the sociology and politics of the north was a historical phenomenon I feel I never learned about in my high school education. But its effect on American society are profound. Think of how “urban” is used as a synonym for black; that’s one of the legacies of the Great Migration.

Bryant roots Rickey in the Great Migration to highlight Henderson’s connection to Oakland and its legacy of African-American athletic excellence, but also to the changes in baseball wrought by its second generation of black (and Latin) stars and the onset of free agency in the 1970s and 1980s.

One of these changes was playing the game with flair, or in Henderson’s case “Rickey Style.” Henderson was famous for the snatch catch in the outfield, and for “picking” his uniform after a home run. He wore a chain with “130” on it—his single season record for stolen bases.

Baseball traditionalists thought Henderson a “hot dog” and thought you should “play the game the right way” and focus on winning. But style and winning baseball are not in conflict. Bryant writes that Henderson “valued style as a spoil of winning. And while this rubbed baseball traditionalists, the vast majority of whom are white, the wrong way “Black fans and players knew that pitting charisma against winning was a false, often racist choice—and a way to punish the Black players for playing with Black style.”

Perceptions of race also clashed with the emergence of wealthy baseball players in the 1970s and 1980s. The advent of free agency compelled owners to pay players what they were worth, and it turned out that those who entertain thousands in the stands and millions on TV were worth a lot of money. And the media of the time reacted to it with jealousy, sympathy for owners and channeling of the jealousy of fans.

This atmosphere, which led to the mid-season strike of 1981, created negativity for all players, but, this fell hardest on African-American players. Henderson was one of them, and Bryant documents the negative articles journalists wrote about him, especially after he was traded to the Yankees before the 1985 season because the A’s did not want to pay his salary when he reached free agency after that season.

Bryant argues that Henderson cared little about what was written about him in the media or about the “mystique and aura” of the Yankee pinstripes. That led him to treat the many journalists covering the Yankees with indifference. Journalists did not take this well and saw it as reason to trash Henderson to their readers and develop outsized expectations for Henderson, blaming him—one of the handful of best players on those Yankee teams—for the failings of the team’s pitching staff and front office.

And unsurprisingly, race played a key role in the growth of the Rickey the clown stories that flourished in baseball circles. But many were exaggerations. For example, the Olerud story never happened, and Bryant is able to trace the origins of the story to another set of former teammates of Henderson and Olerud with the Mets who said it as a joke when Henderson signed with the Mariners. The joke became a legend.

It's one of many legendary stories about the unique personality of Henderson, and reflects a truth about Henderson. He rarely learned the name of his teammates, and even his managers.2 But as the truth gets stretched and exaggerated into story and comedy, it was the racialized aspects of Henderson’s personality that were more exaggerated. Bryant discusses how African-American players could often identify the fake or exaggerated stories based on how often the storyteller had Henderson using his first name in the first person. Henderson did do this, but mostly when he felt he was in a groove and was going to have a good game. “It’s Rickey Time!” Henderson would yell out in the clubhouse, a far cry from the stories.

For many Americans, our understanding of the role of race has morphed and changed since the 1980s. In many circles, especially those of well-educated whites of younger generations, there is a more nuanced understanding that the end of legal segregation did not concurrently end the many barriers to African-American and Latino advancement in the United States. The structural and cultural barriers are just as substantial as the legal barriers and there is more honest discussion of how race really works in many aspects of contemporary society.3

Bryant’s discussion of race in the legend of Rickey Henderson helps to bring this discussion to baseball of my childhood.

Playing Baseball.

Is snatching the ball out of the air, or picking at your jersey after you homer hot dogging it? Or just adding flair to a game that desperately needs some personality?

In the 1980s, the answer of most was that Henderson’s style was that of a hot dog. Today, well, everyone seems to play with some style. There are endless bat flips, fist pumps, elaborate high-fives and dugout stare downs, and they are done by players of all races.

The style of the game has caught up to they style that Henderson played with in the 1980s and 1990s. The complaints that the journalists of the 1980s had about Henderson seem quaint today. One reason they seem quaint is that there seems no reason to believe that “styling” takes away from winning. Plenty of stylish players have won the World Series—including Henderson, who did it in 1989 with the A’s and 1993 with the Blue Jays. One can play baseball with style and be successful, just as one can be successful with a less stylish manner.

A big criticism of Henderson throughout the first decade of his career was that he would take too many days off. Henderson would declare himself unavailable if he had a nagging injury or wasn’t able to give his best effort. The sports journalists of the 1980s were apoplectic, describing Henderson as “immature,” having a “questionable work ethic” and that “it was a shame he wasn’t a better player.” His trade from the Yankees back to the As in 1989 for a handful of relative nobodies4 was greeted as additional by subtraction for the Yankees by New York reporters and risky for the A’s. Henderson went on to go 15 for 34 playoff at bats with 9 walks and 11 steals in leading the A’s to the 1989 World Series. He followed up that season by winning the AL MVP award in 1990.

And the contention that Henderson didn’t really care all that much about baseball didn’t hold up really well. Henderson played until he was 44, taking a series of small contracts with a number of teams to continue his career. And Henderson didn’t stop playing at 44; he played independent league ball in 2004 at age 45 and in 2005 at age 46. He finished his career with the 4th most games played and plate appearances in major league history.

Bryant points out that the practice of resting players when they are less than 100% has become common place in all sports, but especially baseball where “managers, GM, and front offices witnesses attrition masquerading as machismo or worse, as ‘professionalism.’” To avoid this, players sit out when not 100% and are allowed to get back to full health. In the 80’s, the word for Henderson’s behavior was “jaking it.” Today, it’s called “load management.”

Analyzing Baseball

Bryant often quotes Moss Klein, who wrote for the Newark Star-Ledger and The Sporting News, as an antagonist to Henderson. And in one passage in the book, he notes all of the players of the 1980s that Klein said would deserve Hall of Fame consideration when they retired. He never discussed Henderson in this context.

Bill James, the godfather of modern sabermetrics relates that he was once asked if he thought “Rickey Henderson was a Hall of Famer.” James “tole them if you could split him in two, you’d have two Hall of Famers.”

Why did the disciples of Bill James, the proprietors of analytics, take over baseball front offices and become more influential in baseball analysis. One reason is that they focused on numbers, which allowed them to see the greatness of a player like Henderson.

On what did antagonists of Henderson concentrate? It’s not his numbers. Bryant quotes copiously from journalists who covered Henderson during the 1980s and 1990s, and it is rare for one of these long quotes to discuss Henderson’s statistics.

What do they talk about instead? It is a lot about Henderson’s personality and playing style. Much is about the feelings of teammates or attempts to channel the emotions of fans. In modern slang, the focus seems to be on vibes.

It is not uncommon for people’s attention to players to shift to their numbers after their retirement. Think of Ted Williams, whose cantankerous relationship with the media was a key storyline of his playing career, and affected the results of at least one MVP vote.5 Today, those seem odd memories of the old days. The modern Williams is lionized as a baseball star and ace fighter pilot. And his memory has been memorialized in concrete; there is a Ted Williams Freeway in his hometown of San Diego and a Ted Williams Tunnel built as part of the Big Dig in Boston.

Henderson’s numbers are undeniably attention grabbing. He is not only the all-time leader in stolen bases, but also runs scored. He collected 3,000 hits and retired as the career leader in base on balls (since passed by Barry Bonds). What more do you want from a leadoff hitter? Ask Moss Klein, because he apparently wanted something else.

But the focus on numbers does not seem to be just an effect of time passing and memories fading. It also seems to be an effect of the analytics movement that James birthed becoming more of the mainstream of baseball analysis. And as new generations of baseball reporters have grown up with analytics and front offices use more and more analytical concepts to make decisions, more reporting focuses on numbers over personalities.

It is obvious that it is not hard to find sports analysis that focuses on personalities, psychology, and vibes. Contemporary baseball is not immune to this type of analysis. But it seems less than in other sports in part because analytics is so much more established in baseball than in the other major sports. Another reason is that baseball has faded from the spotlight in national attention, which has reduced the “embrace the debate” style focus on the “narrative.” That may be bad for baseball in the attention economy but good for the quality of attention to the sport.6

Bryant’s analysis of Henderson indicates that he has changed little over time. He has always been confident in his abilities and the best player on the field. He has been brash but knows who he is, and that is centered on his Oakland upbringing and caring little about what people outside his inner circle think about him. Heck, he’s even married today to woman he started dating when they were both in high school together.

What Bryant’s book reveals is how much we have changed. And here we means Americans conscious of how the structures of race continually affect our society, including our understanding of sports. We means those of us who enjoy baseball and have an understanding how the game is played. And we also means those of us who to try to analyze the game. In each of these contexts, the country has changed. And it has changed in ways to help us understand how and why Rickey Henderson is a great baseball player and a real human being. And how he is a legend.

Bryant provides basically a census of Oaklanders who migrated as children or are the children of migrants that spans into baseball (Astros third base coach Gary Pettis is one), basketball (Paul Silas, the father of Rockets coach Stephen Silas), entertainment (Silas’s first cousins are the Pointer Sisters), and activism (Huey Newton and Bobby Seale, the founders of the Black Panther Party).

For example, Henderson did not the name of Art Howe, his manager with the A’s in the 1998 season. Maybe he thought he was Philip Seymour Hoffman.

There are obvious limits to how far this attitude goes and that is most demonstrated in the realm of political and political journalism. For example, on no day of Donald Trump’s political career was “why do all these seemingly respectable politicians think that Trump’s open racism is acceptable” was that day’s biggest question in the media. As best as I can tell, the average political journalist never thought about it.

The Yankees haul for Henderson was Luis Polonia, Greg Cadaret, and Eric Plunk. And if you don’t know who those three are, don’t worry about it; they left no legacy in baseball.

Among the legend of Ted Williams is that he is the last player to hit .400 for a season. In 1941, Williams slashed .406/.553/.735 for an OPS for 1.287. Awesome right, but apparently not good enough for 1941 baseball writers, who gave the MVP award to Joe Dimaggio, who had an excellent year and led the league in RBIs, but look at that slash line.

Another way to think about this. Stephen A. Smith and Skip Bayless do not seem talk about baseball all that often, and as a baseball fan, I’m fine with that.