Reaction Post: Hunter Brown's Sinker; Astros Swing Aggression; and Letting the Season Breath

I react to smart articles on why Hunter Brown's sinker has made him effective, if the Astros are being too aggressive at the plate, and letting the season breathe as an analytic principle.

Today, I’ll do something a little different from my usual column-like array of my own thoughts about the Astros. I’ve read three different pieces over the last week that i have found well-researched and argued. Each has been on my mind a great deal recently as I watch the Astros.

There’s a YouTube style of “reaction videos” where a commentator will watch another YouTuber’s video, pausing to offer their own thoughts or comments on the original content.1 I’m going to do something similar here—quoting these articles extensively and then offering my reaction their argument.

I encourage you to click through and read each article in its entirety.

The Reinvention of Hunter Brown by Robert Orr and Ben Ziedman of Baseball Prospectus

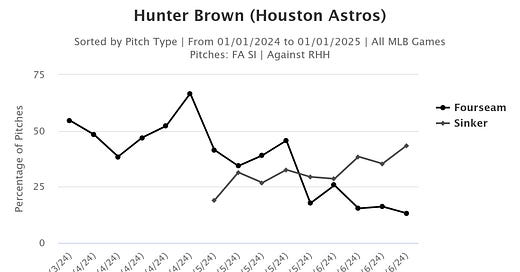

Since throwing that first sinker, Brown has posted a 2.45 ERA over nine starts while steadily ramping up his trust and usage in the pitch, trading in four-seamers for sinkers in basically every start:

It’s seemingly been a one-pitch panacea for all that ails him, but why has this specific pitch—one which hitters have a healthy .333 average against, no less—been a miracle pitch for him?

All of which is to say, Hunter Brown’s poor command—the 12% walk rate before May, the questions that followed him as a prospect, etc.—might not have been a command problem at all. He simply lacked an offering to bring his arsenal together against righties. His four-seam fastball already had more cut (gloveside movement) than other four-seamers, and his secondary offerings didn’t give hitters much else to think about: The cutter/hard slider moved in the same direction as his fastball, and the curve was in an entirely different velocity band than the rest of his arsenal. Crucially, none of his pitches moved towards right-handed hitters, meaning they only had to cover half the zone horizontally against him.

The sinker filled that void; now Brown could come inside to righties with the sinker or pitch away from them with his other pitches out of the same tunnel towards the plate. This concept is illustrated clearly by how Brown finished this AB against Mark Canha during his June 14 start:

Already up 1-2 in the count, the Astros hurler attempts to blow 96 by Canha for the third strike, but Canha fouls it back to stay alive. No worries. Brown comes right back with his hard breaker on the next pitch, and Canha—conscious of the pitch he just saw at a similar speed that ran back towards him—swings too far inside and misses the slider despite the pitch remaining in the zone the whole time:

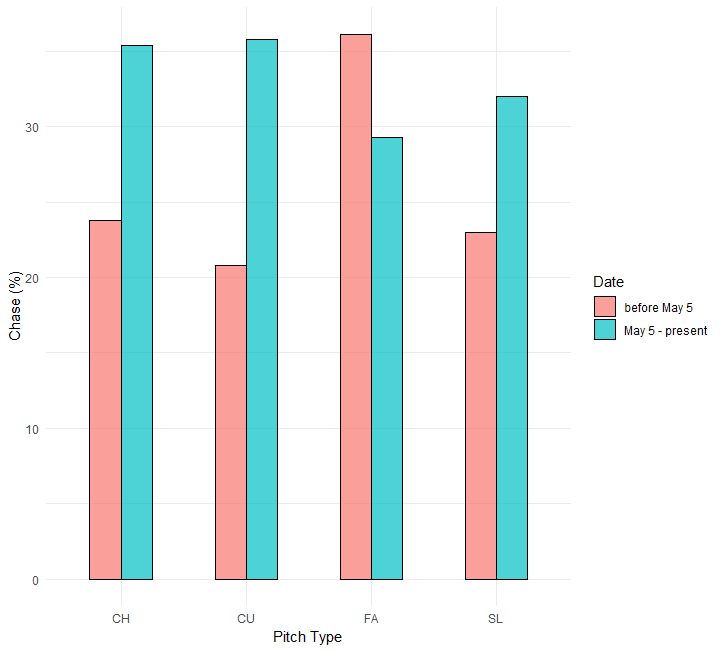

Brown didn’t have to get Canha to chase because the sinker created more space for him to pitch in within the zone, but the tunneling effect works going out of the zone as well. Just look at the chase rates on his pitches before and after the introduction of his new pitch:

And that’s not even counting the 40.2% chase rate he gets on the sinker itself. With hitters more willing to expand the zone, his walk rate has plummeted, from 12.2% before May 5 to just 7.3% after, lending further credence to the idea that his command problems had more to do with an incongruent repertoire than an inability to locate. What the newfound tunnel has done is make precise locations less important to his success; Brown’s pitches need only be close enough to the zone and to each other to sow doubt in hitters’ minds about which direction the ball is about to break for them to be effective.

I had been strongly considering writing something about Brown’s turnaround this season, but decided to shelve it after reading Orr and Zeidman (who is @midzee4 on Astros twitter)—I was not going to have greater insight on Brown that this article.

The ability of Brown to develop another pitch—and a successful one—is another feather in the cap of the Astros player development staff, and especially pitching coach Josh Miller. Miller, who also helped Ronel Blanco develop his devastating new changeup, has had an especially good season as pitching coach.

As Orr and Zeidman show, the development of Brown’s sinker has not only allowed him to have one more effective pitch, but it has helped unlock the best elements of his other pitches.

The key thing to me appears to be how Orr and Zeidman talk about command. Command is not about “filling up the strike zone.” Instead, it is about the ability to fool batters into swinging at pitches headed outside of the strike zone. By getting Brown to have an arm-side breaking pitch to go with his three glove-side breaking pitches (fastball, curveball, and slider), hitters cannot pick up Brown’s pitches as well.

More doubt among hitters leads to worse swings—which I saw pretty clearly in the Canha swings shown in the article.

Astros ‘Swing Too Much,’ Search for Balance with Aggressive Bats by Chandler Rome of The Athletic

“Our whole offense needs to take more pitches,” third baseman Alex Bregman said. “We swing too much.”

Four other lineups do swing more than Houston’s, but none sees fewer pitches per plate appearance, an aggressive approach that has become a trademark across the Astros’ golden era. The 2022 World Series champions also saw the fewest pitches per plate appearance of any lineup in the sport. Last season, only two offenses saw fewer than the Astros.

“We would love to have guys be more passive and walk more,” Cintrón said.

Four lineups walk less than the Astros, whose 7.3 percent walk rate would be their lowest in any full season since 2013.

Only two teams chase outside the strike zone more frequently, perhaps the most disturbing number of some downward trends. Reliance on more unproven hitters has inflated the number, but uncharacteristic zone expansion from Altuve and Yordan Alvarez is exacerbating the problem.

Houston’s lineup does put 30.9 percent of the strikes it sees in play. No other offense does it more. Only three lineups in the sport have a higher overall contact rate. The Astros remain the most difficult team in the league to strike out, but rarely ever put themselves in situations to do so.

No lineup in baseball has seen fewer two-strike counts this season than Houston’s, perhaps because only two swing at the first pitch more frequently. Meyers, for example, has a 44.7 percent first-pitch swing rate. Only eight qualified hitters have a higher one.

“Honestly, if the first pitch of every at-bat for 27 straight at-bats is right down the middle, then I hope everyone swings at all 27 of those pitches, but it’s just not realistic,” Bregman said. “We strike out the least (of any lineup), so I feel that we should know that and not swing as much.”

For years, Sabr-metric thinking taught me that walks were good for hitters and that strikeouts did not matter. But my thinking changed while watching the 2017 Astros, when the front office prioritized reducing the team’s strikeout rate in an effort to get more balls in play. Thanks to some savvy personnel moves and—more importantly—player development that produced fewer strikeouts without the tradeoff of softer contact.

The Astros have followed this model for years, and are usually near the bottom of the majors in strikeout rate. As Rome’s article notes, the Astros continue to have one of the highest contact rates in baseball. But there is a clear decline in the walk rate and an increase in the chase rate across the team this year.

Some of that is personnel. Yainer Diaz is a high-chase, high-contact hitter and he is receiving a higher share of plate appearances this year. Jake Meyers has adopted a more aggressive approach at the plate, and Mauricio Dubon is also a high contact hitter.

The question becomes one of balance. Offenses succeed when they hit good pitches and take bad ones. The Astros have proven over their golden age they do not need to lead the league in walks to be an effective offense. And the Astros offense has been mostly effective this season—they are 5th in the majors in OPS thanks in large part to leading MLB in batting average (.264 for the team).

But Rome is smart to point out the shift in chase and walk rates this season. The concern is that being too aggressive leads to too many swings at bad pitches. The worry is that the Astros are out of balance.

NL East Notes by Joe Sheehan of the Joe Sheehan Newsletter

The Mets’ 2024 season:

0-5 then...

12-3 then...

12-27 then...

15-4

Today, the Mets are 39-39, an unremarkable record for a team projected, at least here, to go 80-82. All those streaks, though, were met with panic or joy, when in fact the 2024 Mets are this year’s best argument for one of my guiding principles: Let the season breathe.

This is what baseball teams do, they look good for a while, look bad for a while. The in-season variance of a baseball team’s performance is bigger than whatever you think it is. The Royals backed up 34-19 with 8-18. The A’s went 17-17, then 12-37. The Yankees have dropped ten of 13 after a 49-21 start and bodies are piling up in the Harlem River.

Breathe. It’s not football. No individual game or series means very much (god, the hot takes after the Mets took two from the Yankees this week...), whether in April or June or even September. The Mets aren’t the .330 team they looked like for a while and they aren’t the .700 team they look like at the moment.2

Obviously, nothing in this article by Sheehan is about the Astros. But everything Sheehan says about the Mets is absolutely true for the Astros as well. The Astros aren’t quite as streaky as the Mets, but they began the season with a big slump, and have recovered over May and June primarily through a six-game win streak in May and the recent seven-game win streak.

I think analysis of baseball is strongly helped by the “let the season breathe principle.” Baseball is weird in short samples and easier to understand in longer samples. It’s a principle that I’ve always tried to use in analyzing baseball and “let the season breath” is an excellent way to express that idea.

Letting the season breathe means seeing the Astros not as the disaster we saw in April or the juggernaut we saw in the Orioles series, but as a .500 team. They’ve had things go their way (the Blanco breakout; Jake Meyers improving) and things go against them (so many pitching injuries). But in the end, the team is dead even.

Of course, that means the big question for the second half of the season is can the team improve over what we saw in the first half. There’s reason to think that they can (c.f. Hunter Brown’s improvement). Here’s hoping.

I’m most familiar with this on history channels. For example, I subscribe to the channel Vlogging Through History, and that channel is almost exclusively these type of reaction videos—the channel’s creator reacting to content from others.

Sheehan’s is a pay newsletter, and he emails 4-5 newsletters a week with his analysis of baseball. It’s excellent and strongly recommended.